“New form of capitalism” emphasises growth over redistribution

Confirming what is not included in the economic plan

On 7 June 2022, the Japanese government announced an economic plan under the banner “new form of capitalism”. The plan, initiated by Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, is intended to steer the economy towards a new growth path by supporting areas such as human resources investment, scientific research, digitalisation (DX) and decarbonisation.

Firstly, before we attempt to identify the key action items that are expected to drive the Japanese economy and businesses in the future, it is important to confirm what is not included in the plan. What is encouraging from investors’ point of view is that the government appears to have effectively given up on some socialist measures after the market had earlier reacted negatively to Kishida’s remarks.

Last year, Kishida had made several concerning statements that forced investors to think twice about investing in the Japanese market. He had called for redistribution of wealth ahead of the presidential election of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party in September 2021 and imposing a higher income tax on gains made through financial transactions was one of the measures he insisted that lawmakers should pursue. Kishida had also indicated that the government would look into abolishing quarterly reporting requirements by public firms in order to change the behaviours of companies that tend to prioritise short term gains to meet the demand of short term investors.

However, the discussion on quarterly reports effectively ended after a government panel concluded earlier this year that the statutory reports should be abolished but be integrated into the quarterly reports required by the stock exchanges. Furthermore, the much-talked-about proposal about imposing higher taxes on individuals with high financial income was nowhere to be found in this plan unveiled this month.

In other words, the plan places greater emphasis on growth policies rather than redistribution of wealth, putting “new form of capitalism” effectively on the same policy path as the one laid down by former prime minister Shinzo Abe.

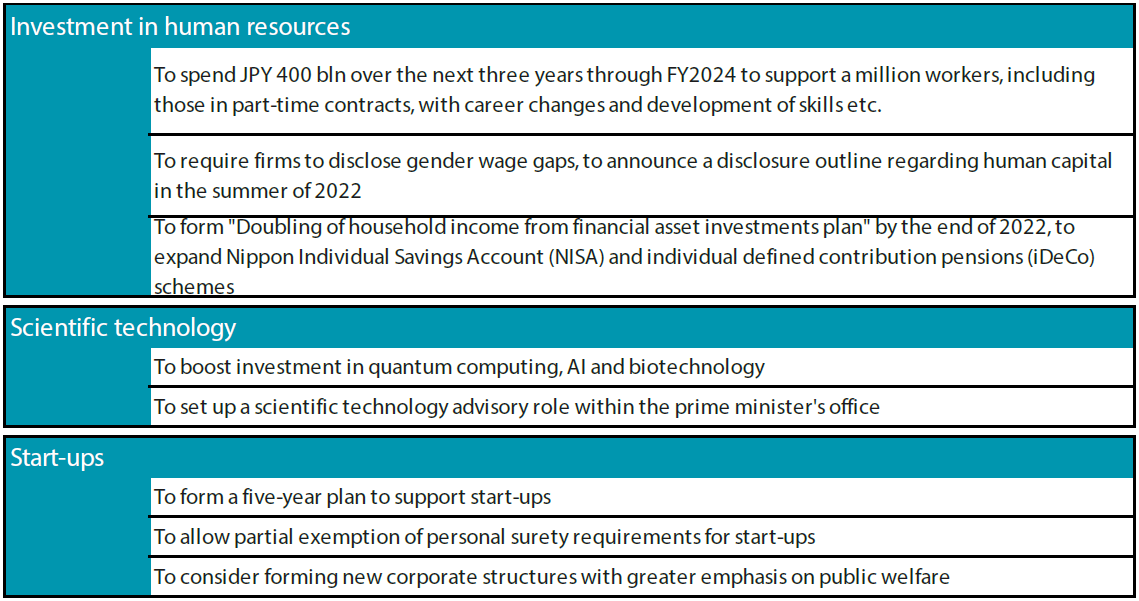

Table 1: Key points from the “new form of capitalism”

Source: Cabinet Office material compiled by Nikko AM

Kishida to retain Abe’s approach to the central bank

Kishida’s approach to the Bank of Japan (BOJ) is also similar to that of Abe under Abenomics. At a committee hearing in Japan’s Diet on 30 May, Kishida confirmed that the policy accord (joint statement) between the government and the BOJ—the basis for the central bank’s accommodative monetary policy in place since 2013—is intact and will be maintained going forward.

The Basic Policy on Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform, an annual fiscal and economic policy guideline approved by Japan’s cabinet on 7 June, shows that the government expects the BOJ to continue maintaining its 2% inflation target.

How the upper house election could impact Kishida’s “new form of capitalism”

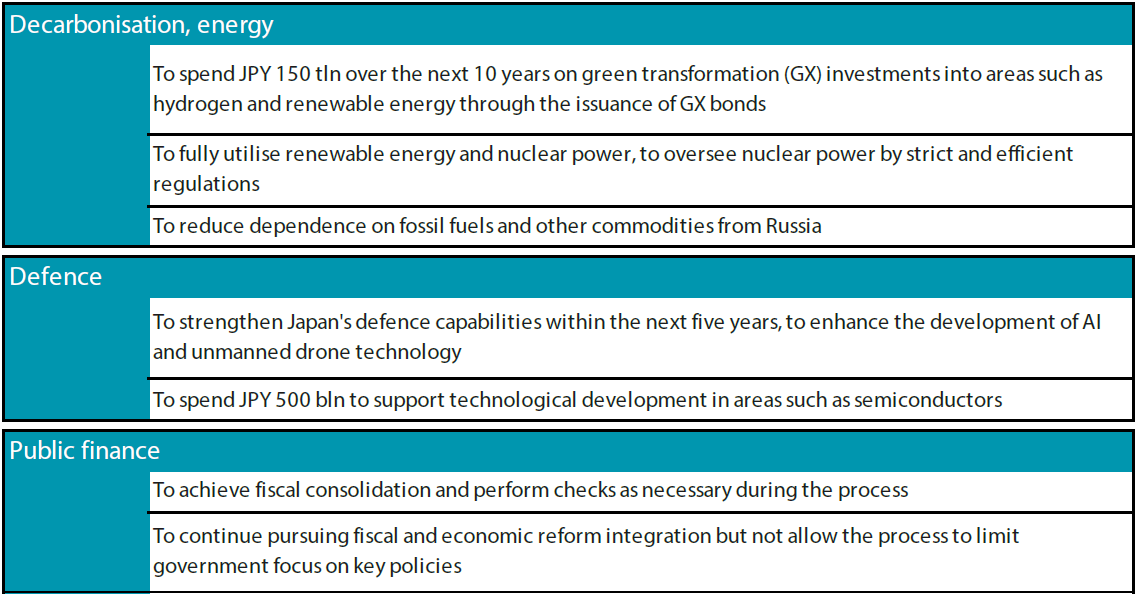

Kishida’s approval rating has risen steadily

According to recent Nikkei poll, Kishida had a 66% approval rating, the highest since he took office in October 2021. This is quite unusual in Japanese politics as approval ratings usually begin falling soon after a prime minister takes office, with the public often quick to conclude that the newly elected leader is too slow to deliver on campaign promises.

Chart 1: Kishida’s approval rating

Source: Nikkei as at May 2022

However, Kishida has managed to boost his rating by focusing on controlling the COVID situation at home. In contrast, Kishida’s immediate predecessor Yoshihide Suga was criticised harshly by pundits and the general public for his handling of the pandemic and had to step down after a year in office.

Therefore, unless there are material changes over the next month, we are likely to see the ruling party win a landslide victory in the upper house election in July, which will effectively allow Kishida to stay in power at least for the next three years as he will be free from national elections.

Strong upper house election win will add clout to Kishida’s policies

A convincing upper house election win for Kishida and his ruling party will have two important consequences. Firstly, Japan will be able to enjoy political stability for potentially an extended period, which may not be the case in other developed economies.

For example, in the wake of the “Partygate” scandal, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson faced a no-confidence vote early in June. Johnson managed to win the no-confidence vote but was left weakened after 41% of the members of parliament from his own party voted against him.

In the US, President Joe Biden is facing a potentially tough midterm election in November. Suffering from sagging public approval ratings, Biden and the Democrats are expected to cede control of the House of Representatives to the Republicans and possibly lose the Senate as well. A Republican House would be enough to block most of the Democrats’ legislations.

Secondly and more importantly, Kishida can take advantage of his political capital after a strong win and take higher-risk strategies, introducing measures which may not necessarily be popular among the public (voters) but could prove to be market friendly, thereby benefiting investors in Japan.

For example, the government could initiate the restart of nuclear plants that have long been left idle after the 2011 Fukushima disaster. One of the bottlenecks towards the restart of plants has been the Nuclear Regulation Authority’s (NRA) approval process, which electric power companies have to clear in order to restart nuclear reactors in accordance with the new safety standards. The government is expected to expedite this process in an effort to ensure energy supply stability, which will also contribute to its goal of achieving carbon neutrality.

Other measures, such as accelerating the opening of Japan’s borders to foreigners (which some voters may still oppose), can also be expected after the election. This should bring positive sentiment to the market as Japan, which closed its borders to tourism for two years, can benefit again from consumption by inbound tourists, who in 2019 spent JPY4.8 trillion, or 0.9% of the GDP.

Whether or not the “new form of capitalism” will be successful or impactful remains to be seen. But if there is one thing we can be sure of, it will be the fact that the economic plan will be implemented by a stable ruling party with much political capital and few distractions.