Nikko Asset Management’s investment experts delve into the risks and opportunities arising from China’s flagging economy and its weakening property sector.

Views from the experts

To gain perspectives on China’s lacklustre economy and its ailing property market, as well as glean insights into a range of Chinese asset classes, Nikko Asset Management has gathered the views of the following fixed income and equity experts:

- David Gan, Senior Credit Analyst (Asian Fixed Income)

- Ian Chong, Senior Portfolio Manager (Asian Fixed Income)

- Truman Du, Senior Portfolio Manager (Asian Equity)

- Eric Khaw, Senior Portfolio Manager (Asian Equity)

We hope that these viewpoints will provide a useful reference to readers as they navigate the increasingly complex Chinese markets.

On the impact of troubled property developer Country Garden

David Gan: Country Garden has already been late on its US dollar (USD) bond coupon payments. It has also extended the maturity of an onshore bond and is reportedly in negotiations to extend the maturities of more onshore bonds. Depending on how they pan out, future developments could cause knock-on impacts to various stakeholders, including Country Garden’s customers, supply chain and creditors (including the US dollar bond market).

For investors familiar with the credit market, it may be worth noting that debt-related developments or restructuring would have a bigger impact on Country Garden’s customers and the supply chain than the credit market. The company’s contract liabilities, which measure the amount paid by customers for properties that have yet to be delivered and its supply chain-related trade and other payables, are both larger than its interest-bearing debt. Debt-related events linked to Country Garden will further erode trust throughout China’s property system, where customers will become less willing to buy properties from other developers, while suppliers and creditors will tighten their credit terms to developers. Furthermore, local Chinese governments could tighten their control over developers' cash in project-level accounts to ensure they keep sufficient cash in those accounts to complete projects. All these effects could tighten Chinese property developers’ liquidity in the near term.

In terms of size, Country Garden is smaller than the embattled Evergrande Group in various ways. But it is still a large issuer. As such, we expect developments related to Country Garden to be felt across the overall Chinese property sector, which will continue to be to be weak in the near term, in our view.

What happens to customers who bought properties from Country Garden?

Gan: Projects by Country Garden are still likely to be completed eventually, although it may be slower than the original timeline. Even though China’s policy support to the overall property market has not been high, there have been measures to ensure that properties are completed and delivered to buyers. In fact, many of the defaulted developers in China over the past two years have continued to deliver properties even after they have defaulted. Nationwide statistics also indicate property completions continue in 2023, even as sales and new property investment are weak. However, even if the property projects are completed, the quality of the finished projects could be significantly worse than the original intentions. The prices of these projects may also drop significantly, in part as developers cut prices to boost sales and cash flow to help fund the project completion. Overall, as a customer, you will still likely get a completed property but with poorer quality. You are also likely lose a significant amount of market value of the home.

Observations on property support measures rolled out by China

Gan: Overall, there has been a stream of property policy easing in 2023 by the Chinese authorities, but the measures up until August were far below the hopes and expectations of the markets. In August, more coordinated easing policies were announced by the national regulators, significantly reducing mortgage down payments and interest rates, and making it easier to be recognised as a first-time home buyer.

Despite recent coordinated measures, we still see policy support as insufficient. In our view, a larger “bazooka” type of support may be needed for the Chinese property sector to improve significantly. However, we expect further policy support primarily through small, incremental targeted measures, such as various types of city-level purchase restriction easing and mortgage policy easing, as there have been indications that the government is not keen to compile a big stimulus for the country’s property sector. These types of small, targeted easing measures have already been ongoing for the past one to two years, but they have not been able to boost nationwide demand for property in a meaningful way.

Are risks spreading to local government financing vehicles and shadow banks?

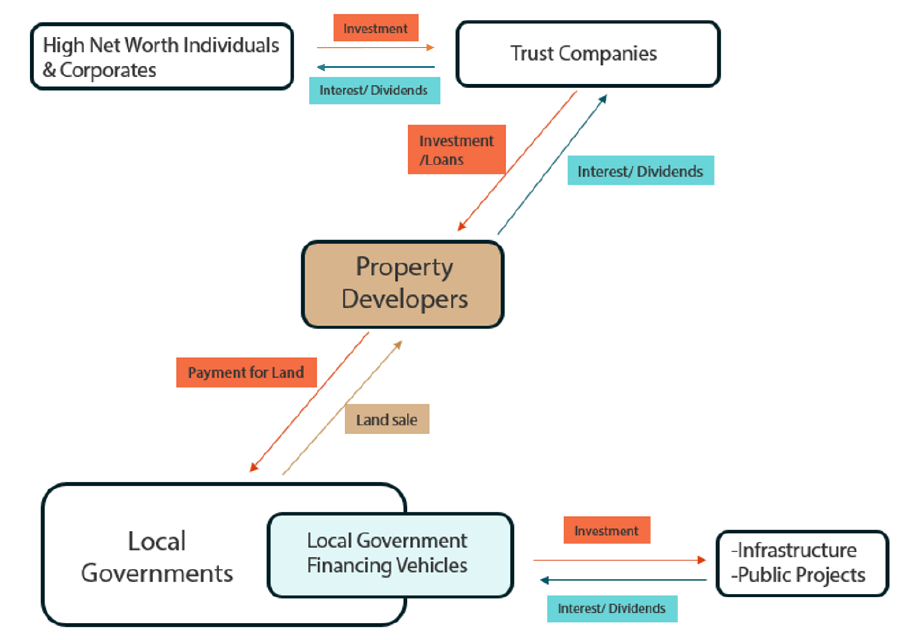

Ian Chong: The property sector makes up about 20–30% of the Chinese economy (including related sectors). There is also an intertwined relationship between the Chinese property developers, the local governments and the trust companies, which manage trust products offered to high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) and small corporations (see Chart 1).

Chinese trust companies lend money to the property developers, which lease and buy land from the local governments. With income, including that from land sales, the local government finances infrastructure and public projects via local government financing vehicles (LGFVs). Of course, the Chinese developers do have other funding sources such as bonds and bank loans. When property developers in China start to default, this chain will begin to be impacted.

Of late, we have already seen a few Chinese trust companies making the headlines for the wrong reasons, such as Zhongrong International Trust Co, which missed payments on its trust products in August. Some LGFVs from the poorer regions or smaller cities may also begin to struggle, especially those that rely heavily on non-tax revenue.

In our view, the Chinese government is unlikely to bail out troubled trust products, as saving HNWIs or less prudent small companies from monetary losses on investments is not a priority. On the other hand, the debts of local governments are of concern, and at its recent Politburo meeting in July, the Chinese government mentioned that it will use a basket of measures to deal with issues pertaining to local government debt risks. These will likely be a multi-pronged approach, involving various stakeholders to extend loans and take some losses. The local state-owned enterprises (SOEs) can also be called upon to help with the funding.

Chart 1: Investment flows and debt surround the Chinese property market

Source: Nikko AM, August 2023

In recent weeks, there has been a lot of speculation on debt swaps that allow the city or provincial governments to issue low interest bonds to repay high interest debt of the LGFVs. Banks too have been extending loans. Though not covered widely in news, there have been trust products linked to LGFVs whose loans have been extended as well. In our view, all the stakeholders in the chain—property developers, local government and trust companies—will have to bear the burden. In all likelihood, a very slow resolution among the stakeholders could result in slower growth for China. But a big collapse in terms of economic growth is not on the horizon, at least from what we are seeing right now.

How will the Chinese banks be affected by the weak property sector?

Truman Du: We believe that the Chinese banks will be affected by the weakening of the property market to a certain extent. But the impact will be limited and manageable, in our view. As we see it, the Chinese banks still have sufficient capital to digest the incoming non-performing loans (NPLs). Loans to property developers only amount to about renminbi (RMB) 14 trillion or just 4% of the total assets of the Chinese banks, which is not a big amount. Of late, some Chinese property developers are seeing a shortage of cashflow, and NPLs linked to them are on the rise. These loans, however, are backed by collateral, and we do not think that a lot of the Chinese developers will default going forward. Chinese property developers in general continue to be supported by the local government, and they still hold reasonable levels of cash.

Elsewhere, mortgage loans currently amount to about RMB 40 trillion or 14% of the total assets of Chinese banks, which continue to regard mortgage loans as safe assets. Today, Chinese households do not borrow a lot of money, and the leverage of mortgage loans is roughly 50% of their total debt. Collateral on these mortgage loans are the homes, and as such, we do not think these loans pose a big risk to the Chinese banks. We could see an increasing amount of NPLs from the property sector, but the Chinese banks could digest these NPLs, in our view.

Moreover, the capital adequacy ratio of Chinese banks stands at 15%, which is much higher than the global average of about 10%. As such, Chinese banks do not need to raise capital unless we see a drastic and prolonged downturn in the Chinese property market. We expect the property market in China to stabilise and recover going forward, and we do not think it is a big issue for Chinese banks.

Outlook for the renminbi

Chong: From the peak of optimism in the first quarter until now, the renminbi has weakened about 8% versus the US dollar, as at end-August. Given that the US Dollar Index (DXY) has also appreciated against a trade-weighted basket of currencies, we want to point out that the renminbi is not as weak as the move in USD/RMB would suggest. Versus a basket of currencies, the renminbi depreciation is actually at a much lower level.

Of late, the Chinese authorities have begun guiding the currency stronger, setting the daily fix of the USD/RMB at stronger levels than what their usual formula would result in. They have introduced a so-called counter cyclical factor in the daily fix, which we have been hearing about in the news. Also, in the middle of August, they began squeezing the liquidity of offshore renminbi. This is a much smaller market than the onshore market, meaning the authorities can exert a significant amount of influence. With this move, the Chinese authorities effectively made the cost to short the RMB a bit higher. This signal has helped to keep the USD/RMB close to 7.3 recently.

When considering the medium-term outlook for the renminbi, it is more important to look at the currency’s fundamentals, such as China’s balance of payments. China runs a current account surplus, and largely, this is a result of the goods trade because China is the factory of the world. The country’s current account surplus is stable and is unlikely to melt away overnight. This kind of dynamic enables the renminbi to weather some level of portfolio outflows, which are currently putting some pressure on the currency.

We do, however, have some concerns about a drop in China’s foreign direct investments (FDIs) in recent quarters. Some multinational corporations have been choosing to expand outside China; this could be related to geopolitics. But there are still companies increasing investments in China, such as electric vehicle (EV) manufacturer Tesla.

On the market front, short positioning on the renminbi currently looks to be at moderate to high levels, signifying a lot of pessimism. Valuations of the renminbi have become more attractive, and if the US Federal Reserve turns less hawkish, the renminbi may benefit alongside other Asian and emerging market (EM) currencies. Additionally, the renminbi, when measured against a basket of trading currencies, looks much more stable versus other EM currencies.

Views on Chinese government bonds and Chinese high yield bonds

Chong: Chinese government bonds (CGBs) are generally considered as natural safe haven assets for domestic investors, and Chinese banks are also known to be consistent buyers. Since the Chinese government has effectively banned implicit guarantees of investment products a couple of years ago, there has been a higher demand for safe assets, including CGBs and policy bank bonds. As a result, the local demand for CGBs has actually increased and there is definitely appetite from domestic investors for government bonds and policy bank bonds.

In spite of the recent negative headlines relating to the renminbi and China, the volatility of CGBs and its correlation with other assets remain low, making them a good component for any portfolio in terms of diversification benefits. Looking ahead, the rebalancing of the Chinese economy will continue and growth is likely to slow, not collapse, in our view. Inflation in China is also low. As such, there is ample room for monetary policy accommodation if needed, and CGBs may be seen as a decent option upon such a development.

Gan: With the recent selloff, the Chinese high yield property segment has already reached very low levels, in terms of bond prices. Increasingly, larger proportions of this bond market segment are trading at distressed prices. Even for Chinese high yield property bonds that have not defaulted, the majority of them currently trade at or below 40 cents to the dollar. This means the market is already pricing a more-than-50% probability of default for many of these surviving Chinese property developers. It can still get worse but arguably, a lot of the downside for this sector has already been factored in, given the already very large negative returns for the past two years.

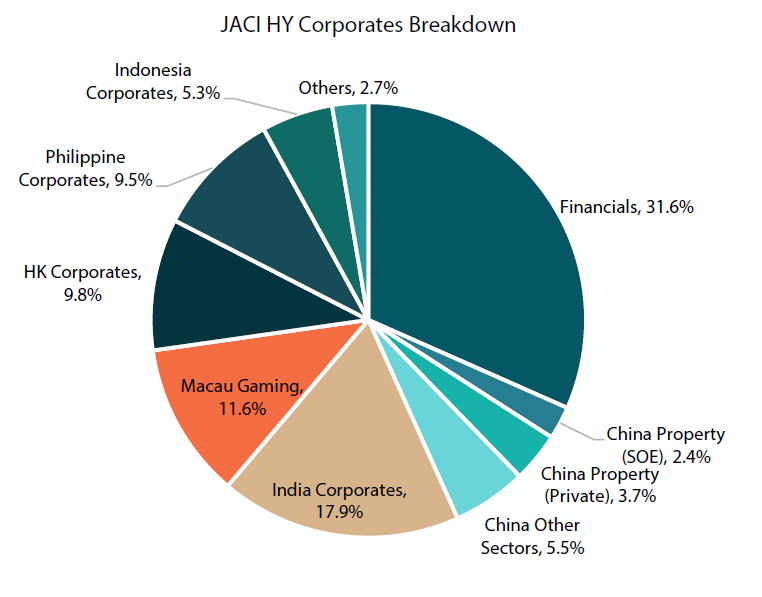

It is also worth highlighting that China property is a much smaller contribution to Asia credit than before (see Chart 2). The sector is also now much more driven by SOEs as defaults from the property segment in recent years came largely from privately-owned developers. In terms of contracted sales this year, state-owned developers and even some of the surviving private developers have performed relatively well even during the downturn this year.

Chart 2: China property remains a small component in Asia credit

Source: J.P. Morgan, Nikko AM, August 2023

Another point to highlight for Asia credit is that while we have seen huge debt defaults from Chinese property developers, the bond default level in Asia outside of China property remains very low. The defaults over the past two-and-a-half years have come almost entirely from the China property sector, while the rest of the Asian high yield market has done relatively well.

Are China equities still worth investing in?

Du: Everyone knows that the Chinese equity market has become very volatile of late. As it is a retail-driven market, its volatility is generally higher than the other markets. Recent elevated volatility is due to the uncertainty of the Chinese economy, especially the weak property market, as well as US dollar strength and renminbi depreciation, which are contributing to capital outflows from China.

Over the last two years, the Chinese government has been restructuring and tightening policies in different industries, such as property, education, internet and even healthcare. China wants to grow in a high-quality manner, and it needs to restructure some industries, while giving other industries more room to grow. The restructuring will be positive for China over the long run, in our view. But in the short term, we could continue to see some challenges with earnings growth in the property, education, internet and healthcare industries. However, the Chinese government has started to slow down its industry tightening measures from the fourth quarter of 2022. There could still be some residual weakness in these industries over the next one or two quarters, but we are very confident that there will a recovery in the affected industries going forward.

Over the longer term, we remain positive on the Chinese equity market on the back of a sustained consumption recovery since the country’s reopening in late 2022. Once we see a stabilisation in the Chinese property market, market sentiment and earnings growth are expected to recover. That is the biggest driver for the Chinese equity market, and we think there is a good bottom-fishing window at the moment for China stocks. We remain positive on innovation-related sectors, namely technology, media and telecommunication (TMT), as well as those related to carbon neutrality and consumption. We remain cautious on cyclicals and financials. In addition, artificial intelligence driven innovation will be a very big theme and driver for the Chinese economy and other global economies. That is why we continue to like the innovation-driven related sectors.

Is China facing structural challenges like Japan did in the 1990s?

Eric Khaw: I do think that China has some long-term challenges, but these are not insurmountable. In the short term, China is facing some confidence issues. A big confidence dampener has been the weak property sector, and if China can turn that around and coupled this with some proper reforms, it can still do well over the next 10 to 15 years.

Of late, China, given its lacklustre economic growth, has been compared to Japan of the yesteryears. There are some similarities, but there are also big differences The first thing that we need to understand is that China today is very different from Japan in the 1990s. To start with, the potential GDP growth rate for China is much higher than Japan.

Second, asset inflation is not as extreme in China today as what we saw in Japan in the 1990s, when property value as a percentage of Japan’s GDP was about 560%. For China, that figure today is only about 260%. More importantly, the Chinese stock market is not in a huge bubble as Japan was back at the start of the 1990s, when it had really heady valuations. This is because foreign investors have always had a very healthy dose of scepticism with regard to China, keeping Chinese stock valuations at a very low level.

Moreover, when the asset price bubble in Japan burst in the early 1990s, the country started tightening monetary and fiscal policies in a very extreme manner. In China, on the other hand, the policy environment is still very easy, and there is room for further easing. In addition, China currently has a stable currency, unlike Japan in the past, when the yen appreciated over 200% in the 1990s.

The news headlines often mention that China has a debt issue. China’s problem, however, is not having too much debt but too little, in our view. You can argue there is a concentration of debt issue in certain areas (like property), but we would point out that the problem for China today is its big savings imbalance. Today, China has one of the highest savings rates within the region, and the savings rate is much higher than the investment rate, which has been impacted by a secular fall in investment demand. What this means is that China, with its excess savings, will need to have higher leverage. If you look at the level of private debt across the board, you will see that it is lower than those of the US, South Korea, Japan and many other countries. Likewise, China’s public debt is only about 71%, according to data of the International Monetary Fund, and is significantly lower than those of Japan and the US. So, there is quite a lot of headroom to increase the country’s leverage rate, in our view.

The bottom line here is that China, with its high savings economy, will need a lot more debt creation and accumulation. The bigger the savings, the more borrowing and lending will have to be done for China’s financial intermediation. Savings need to be transformed either into domestic investment or lent abroad. In the past, China could export its surplus savings abroad. But now, Chinese exports are limited by geopolitics. Spending may be the only way out for the Chinese government.

Another issue that a lot of people have been worrying about is China’s deteriorating demographics due to its shrinking population. The country does have some demographic challenges, with its workforce having peaked several years back. But we are still quite comfortable with China’s demographics for the next 10 to 15 years because the retirement age is currently very low; the female retirement age is 55 while that of the male is 60. These are low by international standards and there is potential room for the retirement age to be raised.

All in all, China's long-term growth plan is very different from the playbook of the West, which focuses on a consumption boost. For China, it is a focus on “Industrialisation 2.0”, centring on EVs, automation, robotics and renewable technology. Take EVs as an example. EV penetration in China, as a percentage of total vehicle sales, is high versus many other countries, and China is currently exporting its EVs overseas. For example, Chinese EV maker BYD’s export numbers on a year-to-date basis are up around 6.5 times, and the carmaker is now selling to 50 countries.

With China’s Industrialisation 2.0, we believe that there will be a lot of growth potential for the country and opportunities for investors. But China needs to reform to shift its economy away from the dependence on property and infrastructure to high-end manufacturing and consumption. The country also needs to reform the financing channel of its local government to be less dependent on land sales. Looking ahead, we believe China can carry out its reform successfully, and the world’s second largest economy can still grow fairly well over the next 10 to 15 years.

Key takeout

- We expect the China property sector to remain weak as markets await stronger support from the government.

- China’s economic growth is likely to slow but not collapse.

- The renminbi could depreciate further versus the dollar, but we expect it to stabilise in the medium term.

- We remain positive on innovation-related equity sectors, namely TMT, as well as those related to carbon neutrality and consumption.

- China is focused on Industrialisation 2.0, centring on automation, robotics and renewable technology, and we expect innovation to drive its economy.

References to any particular security is purely for illustration purpose only and does not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security or to be relied upon as financial advice in any way. There can be no assurance that any performance will be achieved in any given market condition or cycle. Past performance or any prediction, projection or forecast is not indicative of future performance.