Japan’s “Show Me the Money” Corporate Governance: 2Q Positive Profit Surprise

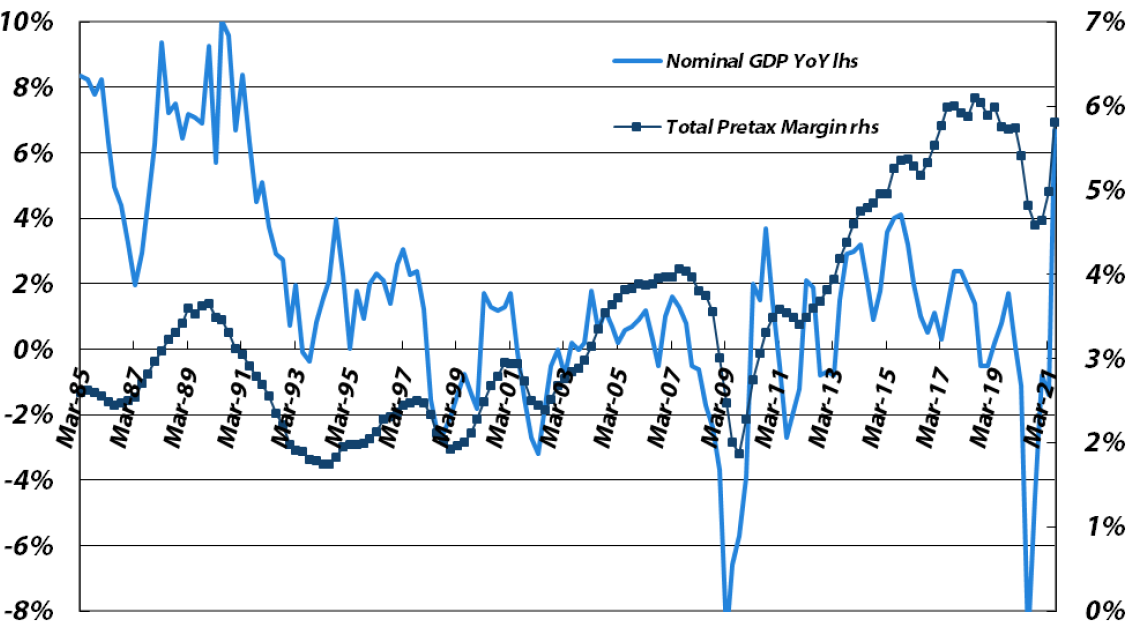

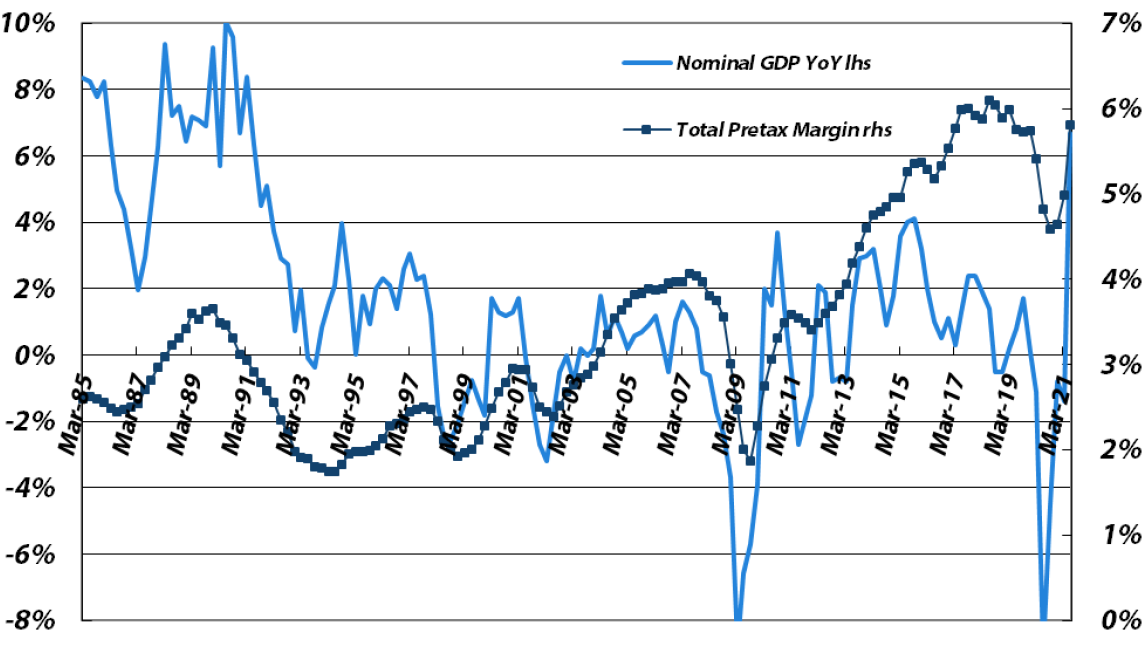

The just released 2Q CY21 data on aggregate corporate profits in Japan was surprisingly positive, as the overall corporate recurring pre-tax profit margin surged relatively near its record high in the 3Q CY18. This was greatly supported by both the non-financial service industries and manufacturing sector, with the latter virtually matching its record high. Could we return to the upward trend since 2005 (despite the long term low GDP growth) and hit new highs soon?

Four-quarter Average Pretax Profit Margin vs. Japanese Nominal GDP YoY Growth

(for all large non-financial companies, not just listed ones)

Sources: Japan Ministry of Finance, Bloomberg, data through CY2Q21

Sources: Japan Ministry of Finance, Bloomberg, data through CY2Q21

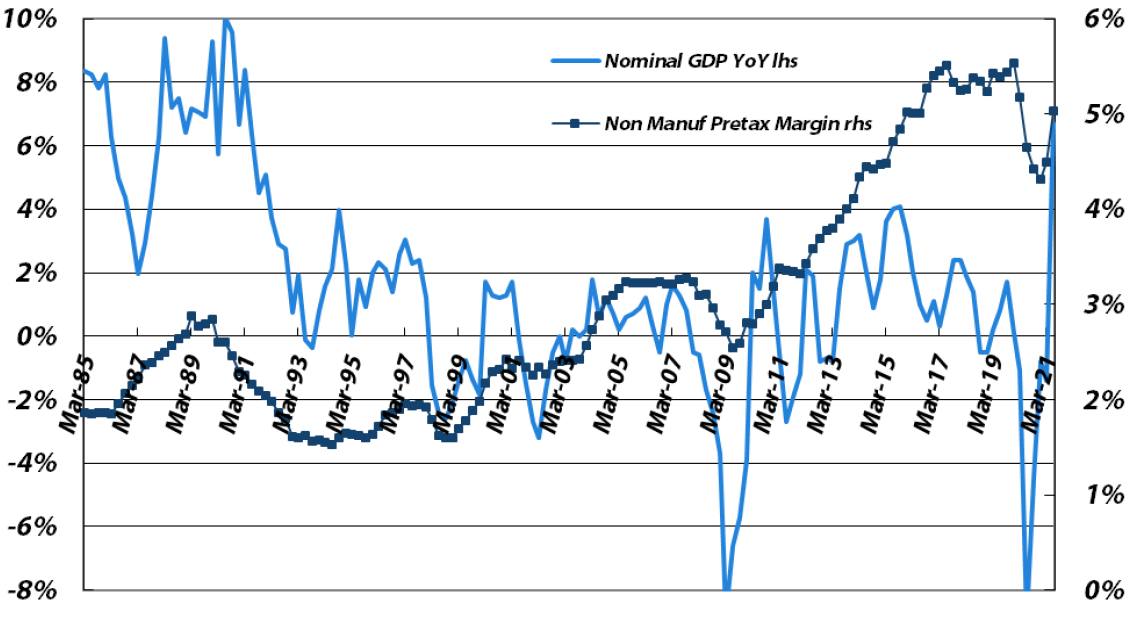

Non-manufacturers (excluding financials):

Sources: Japan Ministry of Finance, Bloomberg, data through CY2Q21

Sources: Japan Ministry of Finance, Bloomberg, data through CY2Q21

Manufacturers:

Sources: Japan Ministry of Finance, Bloomberg, data through CY2Q21

Sources: Japan Ministry of Finance, Bloomberg, data through CY2Q21

One should also note that the Ministry of Finance statistics cited in this report do not cover post-tax income, and due to corporate tax cuts a few years ago, the overall net recurring profit margin (which is unfortunately unpublished) has expanded even more sharply than the pre-tax data shown above, allowing shareholders to benefit from higher dividends and share buybacks. Also due to buybacks, EPS has been (and still is) growing even faster than net profits.

As for dividends, they have risen rapidly too, more than doubling since 2013 for the Tokyo Stock Exchange Index. Crucially, in order to stabilize Japan’s future, an Equity/Dividend Culture must be better established among retail investors in Japan. There have been gradual image improvements for equity investing since the speculative burst of the 1980s bubble, but achieving a structurally higher dividend payout ratio would be a master stroke as most domestic retail investors don’t accept buybacks as a primary reason to invest long-term in Japanese equities whereas they adore dividend income, especially given prevailing flat or negative interest rates. Clearly, much progress has been made regarding dividends in the past few years, but much more is needed on this front.

As for the corporate view on dividends, even the most reluctant would now likely agree that their prior resistance to corporate governance reform was unwarranted and should realize that holding excess cash is equally unwarranted now and that Japan’s dividend payout ratio is rather low by mature country standards. Unfortunately, many corporations prefer buybacks to dividends for exactly the wrong reason: dividends are sticky and hard to cut, whereas buybacks can drop to zero with minor embarrassment. But this argument implies to current and potential shareholders that these Japanese companies have little confidence in their future, which is somewhat embarrassing and likely far too conservative. Indeed, in order to be effective as a support for share prices, dividends need to be communicated as being maintained at a high level even in a recession, barring grave financial threats to the company. This should protect the Nikkei from falling too far during troubled times and reduce fearful volatility in the long-term. Such would crystalize the domestic equity culture that Japan has long-tried to instil, just like most of the rest of the developed world, and also would entice foreign investors back into Japanese equities.