The first Global Investment Committee (GIC) meeting of 2025 was held on 10 March.

Key takeaways from the meeting are as follows:

- Volatile market conditions may be the new normal. However, opportunities may emerge due to uncertainty and greater differentiation among firms and economies.

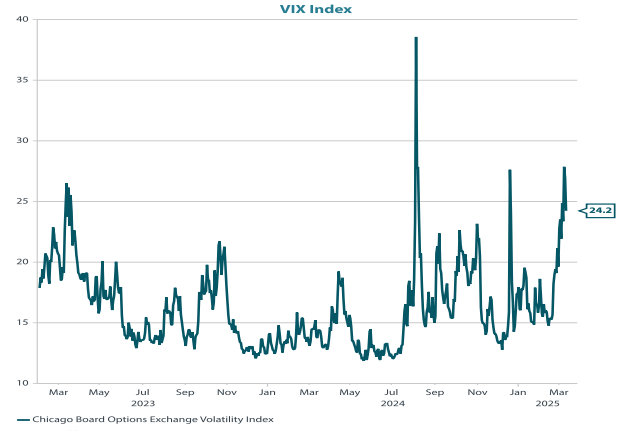

- We modestly downgraded our near-term US growth outlook while upgrading our inflation outlook but continue to see positive growth in the US over the year to come. Though not our central scenario, we see elevated tail risks of recession, as well as of resurgent inflation in the event the current tariff tit-for-tat escalates into a trade war. Although the Federal Reserve (Fed) has signalled that its rate cut cycle is not yet complete and some weaker sentiment signals have emerged, inflation remains mildly above the Fed's target, even as unemployment remains relatively low. We have modestly upgraded our FOMC policy rate outlook.

- Anticipation that the new US administration will implement fiscal stimulus has recently been offset by the uncertainty caused by growth risks from the purported methods of financing such stimulus, namely tariffs and cuts to federal jobs. Although our central scenario is for the US to ultimately eschew policy measures that could hasten recession, uncertainty in the interim may limit the potential upside in US stock valuations from here.

- Meanwhile, we observe potential turning points in Europe and China equities that may serve as opportunities to diversify global portfolios. We continue to look for assets resilient to inflation and external demand shocks to hedge tail risks. We remain constructive on gold and the Japanese yen as portfolio diversifiers.

- We continue to favour Japanese equities due to ongoing indications of Japan's structural reflation and relative undervaluation. The risk premium offered by Japanese equities is now equivalent to that of the US. Within this context, we continue to look for value among Japanese domestic demand-related stocks. Nonetheless, we see uncertainty over trade and market gyrations likely to persist in the Japanese stock market. Therefore, in the near term, we would follow the example of domestic investors and capitalise on volatility-fuelled dips, anticipating resilience from the market.

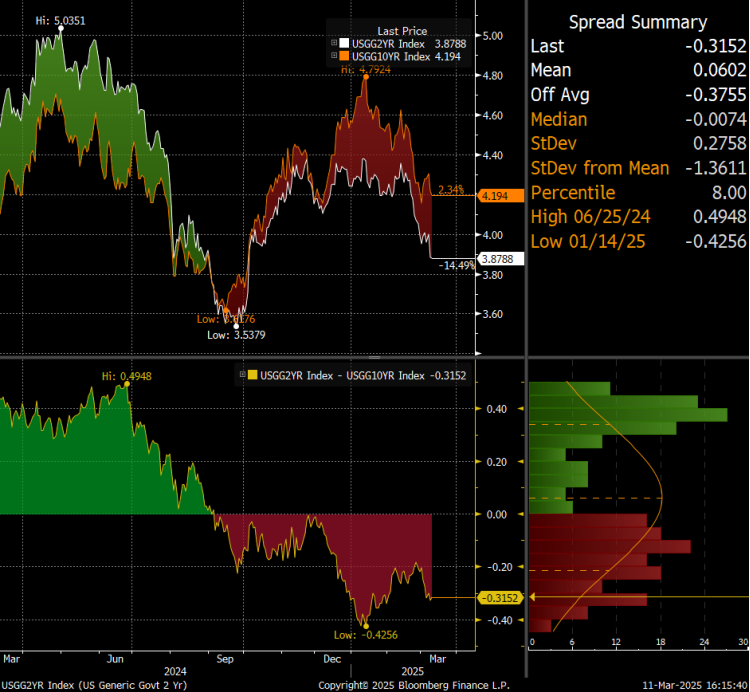

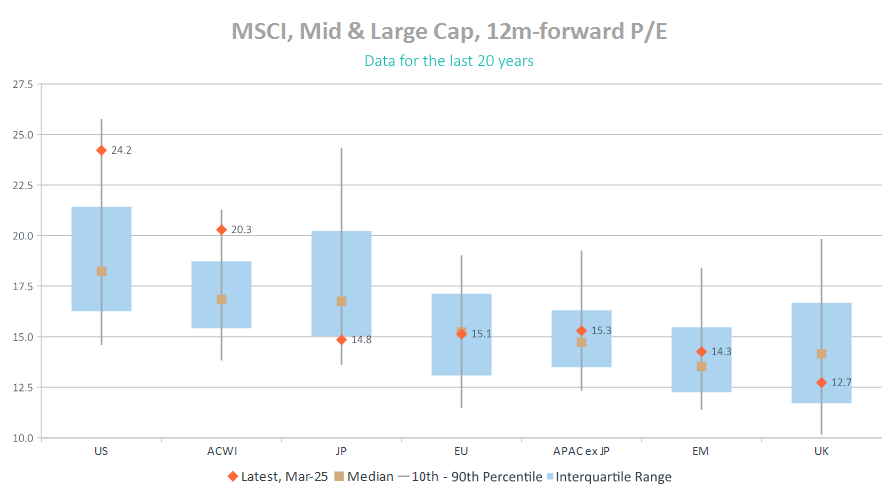

- The correction in short-term US interest rate expectations appears to have resulted in some bull-steepening of the US yield curve, as longer duration bonds remain comparatively out of favour with the US term premium becoming more deeply entrenched. We remain cautious over fiscal risks and trade uncertainty as potential disrupters of the longer end of the US yield curve later in 2025. For now, budget negotiations may take some time, including (at time of writing) a stopgap funding measure and beyond this, a budget resolution. In the short term, the drawdown of Treasury reserves may help keep liquidity intact and contain the upside of longer-term bond yields. However, US indebtedness is at its highest since the Second World War and uncertainty over trade and budget negotiations may keep the term premium intact for some time.

- At the time of writing, promises of more “proactive” and robust (“from first kilometre” to “last kilometre”) macroeconomic policies at China's National People's Congress make us cautiously optimistic over equity market recovery. In the absence of such proactive stimulus, Chinese growth could struggle to meet the annual 5% target. That said, the extent of the authorities' support for consumption is likely to remain uncertain until the endgame of US tariff negotiations becomes clearer. Given recent US criticism levelled at bilateral surplus-holding economies, China's stimulus measures may prioritise fiscal easing over renminbi (RMB) depreciation.

Q1 Takeaways: The US shifts from “exceptional” to “high stakes”

As the GIC looked back over the past quarter, we observed that, as we had foreseen in the previous quarter, US growth had remained robust even though volatility had risen. With the start of the new US Administration, US stock markets have re-rated from their peak valuations, shifting away from a narrative of “US exceptionalism” towards the pursuit of potentially high payoffs through increasingly risky bets on future growth. On the manufacturing side, what appeared to be decoupling in manufacturing (relative US ISM versus developed country PMI's) now appears to have been front-loading of US imports in anticipation of tariffs to come.

Meanwhile, stocks have been gyrating on daily shifts in messaging regarding US tariffs while anticipated job losses at US departments and agencies have invited fears of a slowdown in US employment, and therefore growth. By the end of 2024, the bond market had priced out many of the Fed rate cuts that were anticipated in the middle of the year. However, some anticipation of multiple cuts originally priced in as of Q3 2025 has started to re-emerge, as uncertainty has grown. Over the first quarter, the market went from pricing in less than two Fed rate cuts to fully pricing in three cuts as at 10 March.

In Japan, reflation continued at a faster pace than anticipated, with signals that spring wage negotiations are likely to show strong gains to counteract the surge in food prices in particular. As Japanese inflation is no longer purely a cost-push imported phenomenon, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has signalled that it will continue to withdraw stimulus, with markets re-rating the extent of the hike cycle. The yen has continued to climb from extremely under-valued levels.

European growth , after bottoming, received some support from both rate cuts by the European Central Bank (ECB) and new signals of fiscal expenditure, including but not necessarily limited to defence, in Germany. This support has led to a reassessment of European stock-markets , which are now re-rating their previously low valuations.

Similarly, an ultra-bearish picture for Chinese stocks in 2024 gave way to a substantial tech-fuelled rally, with potential for government stimulus seen as one contingent factor for additional gains. Promises of a more “proactive” and robust (“from first kilometre” to “last kilometre”) macroeconomic policies from the NPC have sparked enthusiasm in the markets about the prospects of more front-loaded fiscal stimulus and continued support for Chinese growth .

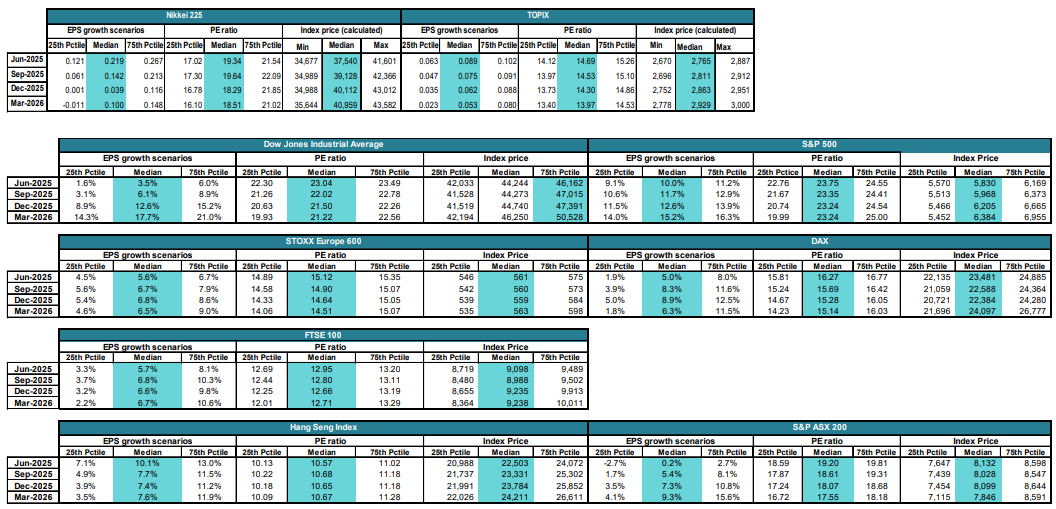

Chart 1: A regime shift is afoot as stock volatility increases

Source: Nikko AM

Global macro: why “higher stakes”? Tariffs, job cuts are risky strategies

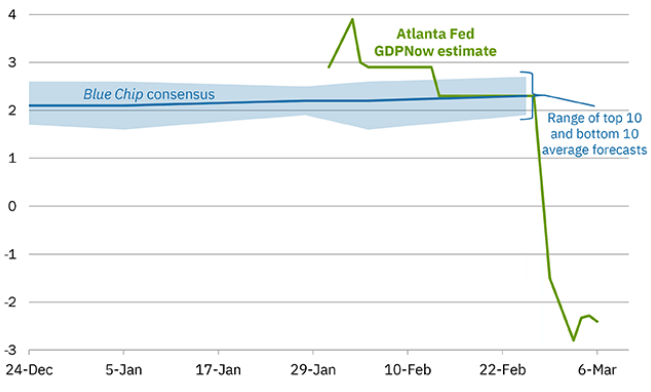

US: Macroeconomic indicators remain mostly resilient, but it is what lies ahead that gives markets pause. As we see in Chart 2, unemployment remains below the Fed's Survey of Economic Projections, and core inflation is mildly above the Fed's 2% inflation target, though contained. These indicators appear to show that Fed rates are “in a good place” for now, supporting the Fed's gradual approach to reverse restrictive policy. This however contrasts with the Atlanta Fed's GDPNow high-frequency indicator, which plunged in March (see Chart 3).

Granted, the GDPNow indicator collapsed mostly because of a decrease in net exports, while consumption and real private domestic investments remained firm. This shows the potential for external shocks to affect the US, which represents a substantial difference from the previous narrative of US exceptionalism in growth.

GIC voters provided diverse views at the March meeting. Below we present a selection of these views, which contributed to the downgrading of our near-term US growth outlook. Despite the adjustment in views, there is still optimism among voters that the US could avoid a recession over the coming year.

- Looking past the noise, the underlying economy looks strong. So, we look through the chaos caused by tariffs and the “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE) cuts (“the ideas are good, but the problem lies in the execution”).

- There remains a risk that firms may hold back on capital expenditure in the face of greater uncertainty. This could lend some bearishness to the growth outlook.

- Confidence looks shaky. Uncertainty may be creating the conditions for a turning point. We are assessing the environment from the sidelines rather than making big investment decisions.

- Worries over tariffs may be priced in. The rise in the bond market term premium starting last September shows that the markets had already anticipated what may happen with a Trump Presidency. Even with equities gyrating, the bond market may have already moved in anticipation and is showing some “fatigue” over the tariff theme. DOGE cuts are still a wild card for the economy.

The focus has shifted to uncertainty about Washington's high-stakes strategies on trade and government jobs and away from the fiscal stimulus measures the new administration could implement. Although our central scenario is for the US to ultimately avoid policy measures that would hasten recession, the tail risks—including that of a recession—have become even larger. Some of our voters think that the chances of a recession have risen to 25%.

Chart 2: On one hand, PCE inflation show Fed rates “in a good place”

Unemployment and headline PCE inflation

Source: Federal Reserve of San Francisco

Chart 3: On the other, GDP growth “nowcasts” are concerning

Evolution of Atlanta Fed GDPNow real GDP estimate for 2025: Q1

Quarterly percent change (SAR)

Date of forecast

Sources:

Blue chip Economic Indicators and Blue Chip Financial Forecasts

Note:

The top (bottom) 10 average forecast is an average of the highest(lowest) 10 forecasts in the Blue Chip survey.

Source: Federal Reserve of Atlanta, https://www.atlantafed.org/-/media/Images/cqer/research/gdpnow/gdpnow-forecast-evolution.gif

Japan: Real interest rates remain very low (real rates minus real growth remains in negative territory, despite the BOJ's rate hikes to date). Meanwhile, wages are on the rise again, and the Shunto spring round of wage negotiations may result in another year of significant increases. Negotiations are expected to deliver a healthy “base up” of 4-4.5%, which may reinforce domestic consumption. Therefore, the GIC's base case is that the macroeconomy will continue expanding and the BOJ will keep hiking rates. But given global uncertainty, the BOJ will be slow to remove accommodation.

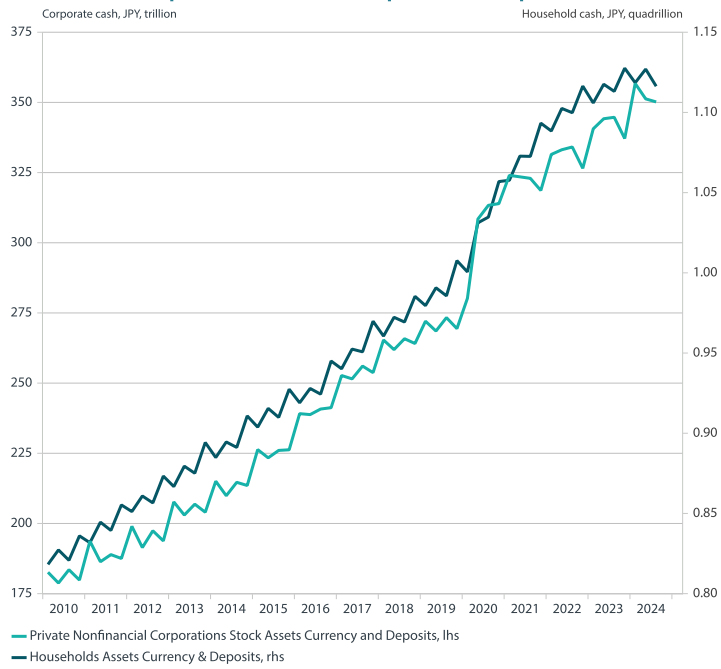

A factor providing significant structural support is the cash corporates and households can use to boost the real economy, and there are signs that excessive cash savings appear to have peaked (see Chart 4). Bankruptcies among Japanese companies are rising, but many of these have been attributed to firms' inability to weather the shift in labour force dynamics that have resulted in employee shortages. This shift in labour force dynamics may allow “zombie” companies, which previously received government support to prevent increases in unemployment, to exit the market without negative ramifications to households.

Meanwhile, the overall unemployment rate is very low. Labour productivity (per capita GDP) is generally improving, which may also add to the case for the BOJ to hike rates to achieve a more neutral policy. Regarding external shocks, US policy remains a risk. However, Washington is not particularly targeting Japan. In the event that reciprocal tariffs become the main strategy, the disparity between Japan and US tariffs is not significant, potentially limiting the impact on Japan. However, the US trade deficit with Japan is substantial so the risks of tariff threats remain, even if such threats end up being “cheap talk”.

Chart 4: Both Japanese household and corporate cash holdings appear to have peaked

Japan Household and Corporates Built Up Cash

Source: Nikko AM, BOJ

Eurozone: the region's growth could be at an inflection point, with the potential for the relaxation of the German debt brake, which could lead to increased dissaving by both German households and firms. Such a change in Germany could have significant implications for Europe. The key question now is how fiscal stimulus can impact European growth. Tariffs are still a significant risk for Europe. There has also been a significant shift in attitudes towards defence and infrastructure, such that fiscal spending may revive economic activity. An uptick in economic activity has not yet been observed, though there could be momentum if spending bills are approved.

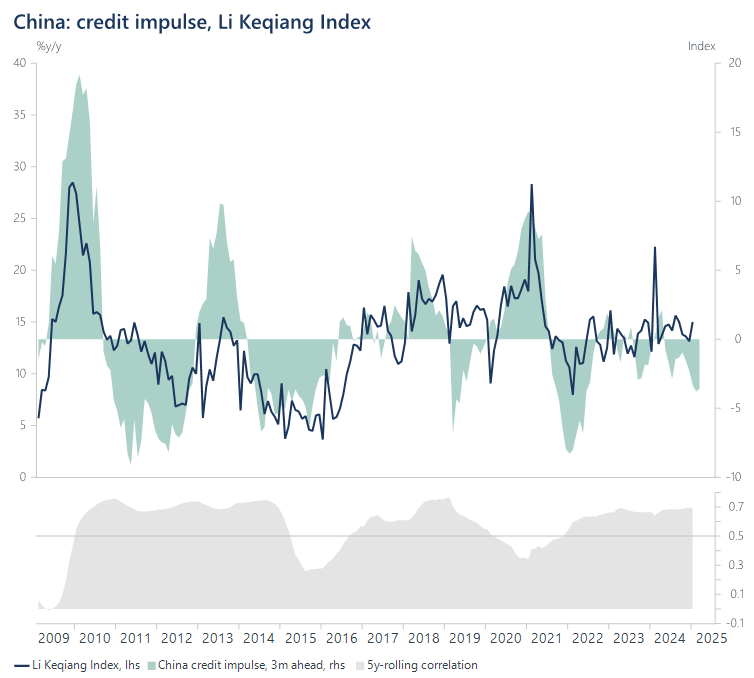

Chart 5: Chinese fiscal impulse still lagging, but some green shoots in economic activity

Source: PBOC, NBS, Macrobond

China: The National People's Congress (NPC) still aims for 5% growth for the year. To achieve this, they have augmented the fiscal deficit, resulting in an almost 2% fiscal boost. China's finance ministry has been active in issuing special Chinese government bonds (CBBs) in anticipation of US tariffs and geopolitical risks. So far, the 20% tariffs the US imposed on China remain an improvement on the 60% originally feared. Our central scenario is that the end outcome will involve negotiation and compromise rather than an all-out trade war.

Meanwhile, there has been some front-loading of exports that could taper off once tariffs take effect. However, for growth to pick up again and reach the 5% target, more fiscal spending will be needed. Chinese inflation is very low, with domestic inflationary pressures being limited despite the low base effects. But there are some “green shoots”: spending in February during the Lunar New Year showed that consumers are willing to splurge on smaller-ticket items.

Meanwhile, the technology-led equity rally remains a complex issue for China's real economy. Adoption of AI could mean reductions in labour demand if task-oriented jobs can be automated, which is disinflationary/deflationary and may then require additional consumer-focused stimulus. China's bond market did not respond positively to the People's Bank of China (PBOC)'s decision to postpone a rate cut. The PBOC's language—it said it was looking for the “right time to cut”— appeared to send a message that further cuts would be delayed. The message may have been motivated by the PBOC's interest to ensure fair policy rates. The central bank may have judged that the decline in long-term yields had gone far enough, especially after 30-year Chinese government bond yields fell below those of 30-year Japanese government bonds (JGBs). The PBOC may have seen an opportunity to adjust the bond market, despite maintaining an overall accommodative stance.

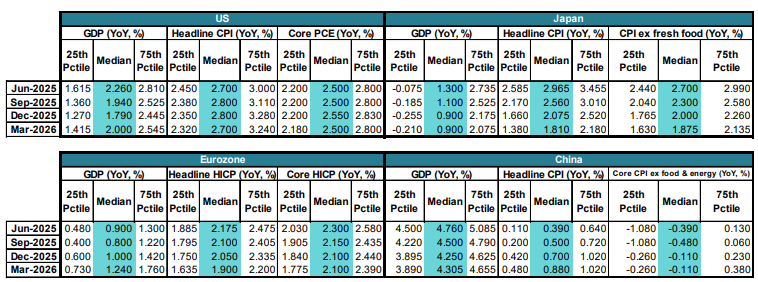

Outlook guidance: macroeconomics

The GIC foresees US growth to likely remain positive over the next year, with an inter-quartile range probability between the low 1% level to the mid-to-high 2% level, anticipating a slowdown from the 2-3% growth range that the US has recently realised. Part of the change in view is due to stubborn inflation. The GIC sees core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) likely hovering near, if not slightly exceeding, the Fed's 2% target over the next year. Core PCE is expected to fluctuate within the low to high 2% range, with only mild moderation from current levels, even despite some moderation in headline CPI from current levels near 3%.

Japanese growth in 2025 is foreseen as remaining firmly above the potential growth rate (0.5% in the latest BOJ estimates), but the near-term trade uncertainty may lead to some gyrations. There could be quarterly dips into negative territory over the next year. On the upside, 2-3% YoY growth may be achieved in any given quarter as another year of historically strong wage hikes stimulate domestic consumption. Inflation is anticipated to remain on the high end as well, and the BOJ may need to extend its rate hike cycle beyond 2025 to keep real growth on a positive trajectory. Headline inflation is seen fluctuating between the upper 1% and higher 3% handle (in part dependent on the yen and import cost pass-through) while core inflation is expected to keep between the upper 1% to near 3% level. The GIC does not anticipate a return to deflation.

Eurozone growth meanwhile may start to show some upside potential; although the median outlook is still sub-1% for most of 2025, we may be at an inflection point. We may leave behind negative growth risk, with the upper end of our inter-quartile range seen accelerating toward the end of 2025 and growth seen in a 1% range between 0.73% to 1.76% YoY in the March quarter of 2026. Core European inflation is anticipated to keep between the upper 1% to upper 2% range, showing some moderation over the next year.

Chinese growth may start near 5% but begin tapering off gradually as the impact of tariffs are felt. There may be some upside in Q2 and Q3 growth from basis effects considering that growth in 2024-Q2 and Q3 was weak. There may be some upside risk in the form of fiscal stimulus not yet priced in – China has “dry powder” it may use once the full extent of US tariff measures likely to be enacted are known. The GIC foresees Chinese headline inflation fluctuating around 0.5% for the rest of the year.

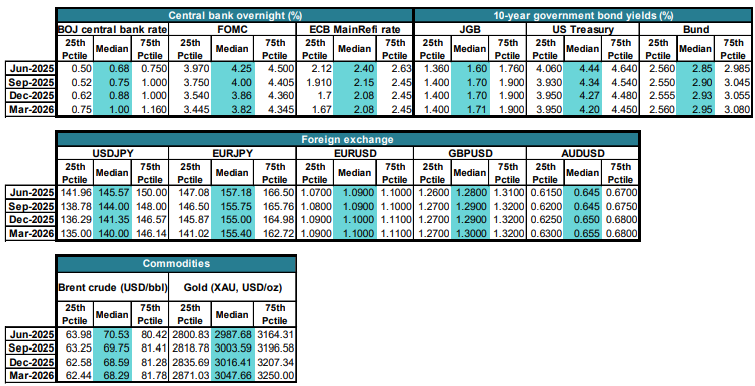

Interest rates: mind the term premium

FOMC: though we foresee a higher-for-longer scenario, the GIC expects the Fed funds rate to drop below 4% by December 2025. That said, our inter-quartile range both factor in the possibility of no cuts as well as that of a drop below 4%, possibly by mid-year, if growth and inflation slow more than anticipated.

BOJ policy rates: with inflation riding higher than expected, the GIC anticipates that the BOJ will hike interest rates to 1% by March 2026. The inter-quartile guidance range includes the possibility of interest rates reaching 1%, possibly within 6 months. Our main scenario is for the BOJ to maintain its twice-yearly pace of hikes, with one mid-year and another closer to year-end. Of course, uncertainty remains due to the risks posed by external shocks to growth, as well as upside risks from imported inflation.

ECB: The GIC anticipates that the ECB will continue to cut interest rates. However, the rate cuts may slow in the latter half of the upcoming year if fiscal policy stimulates growth. Indeed, if there is a true shift in attitudes around fiscal spending, we may see higher growth. The market had originally priced three cuts from the ECB prior to the recent bond market moves. The market is now pricing in less than two rate cuts, as it has adjusted the fiscal premium in the long end of the yield curve.

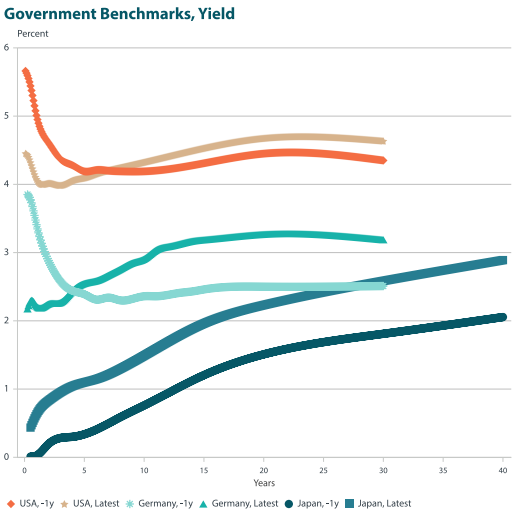

10-year interest rates: the return of intra-currency carry

One GIC voter sees the recent moderation in bond yields as an indicator that we are currently running a much greater risk of recession than before. The steepening of yield curves appears to be a theme across geographies amid prevailing uncertainty. The term premium remains worth watching; there is a trade-off going on between the inflationary risk of tariffs and fears of slower growth. The pivot point for US Treasuries was in September 2024, when the yield curve inversion reversed and the term period started building (see Chart 6). There was a very recent and significant re-rating of longer-term German Bunds, which contributed to the rapid steepening of the European yield curve .

The US credit market remains well-supported despite gyrations in the stock market. Part of this may be due to supply—especially in the longer-end—and the fact that carry remains intact as the Fed cuts rates. It must be noted that issuance in the high yield market has been concentrated in the shorter end, so the market is not as vulnerable to the rise in the term premium. That said, the Nikko AM Credit team is prioritising higher quality investment grade credit because of the increase in overall uncertainty and the likelihood that high-grade credit will weather market volatility more successfully.

In Japan, a 40-50 bps re-rating took place in the long end of the JGB yield curve , with the 10-year yield moving from around 1% to above 1.5%. Some of this could be due to supply-demand irregularities as institutional investors prepare to close their books ahead of the fiscal year-end. That said, inflation is higher than expected, and this may continue to exert upward pressure on long-end JGB yields. However, this also means it creates carry opportunities for domestic investors.

Outlook guidance: We foresee the return of term premiums to be a persistent theme over time. We see the 10-year Treasury yield remaining above 4% even as the Fed delivers additional rate cuts. A drop below 4% is seen as probable only if the Fed delivers cuts that take the policy rate to the mid 3% range. Despite anticipated ECB rate cuts, we see longer-end Bund yields edging higher. The GIC foresees an inter-quartile range for the 10-year Bund yield over the next year between 2.5% to the low 3% range. The GIC expects the 10-year JGB yield to creep higher over the upcoming quarters, ending March 2026 between 1.4% and 1.9%.

Chart 6: The return of the US term premium

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 7: Steeper yield curves across geographies

Source: Nikko AM, US Treasury, Macrobond, JBT

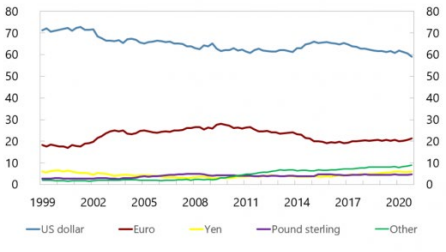

Foreign exchange: slow reversal of dollar strength, yen the main beneficiary

Current uncertainty over US tariffs, particularly those aimed at reducing US trade deficits, as well as Washington's stance on overseas aid, defence expenditures and other cross-border spending point to a potential decrease in the flow of dollars heading into overseas circulation. This will potentially decrease demand for dollar assets, especially foreign reserves. The IMF points out that the dollar's share in global reserves by far outweighs the US share of global GDP, and maybe for this reason, dollar-denominated reserves have been declining for several years, well prior to the current US administration (see Chart 8). This trend could eventually become problematic as the US seeks to fund ever-larger fiscal and current account deficits.

GIC voters are confident that the US dollar will likely come under pressure, in both the near and long term, with yen expected to be the main beneficiary.

A selection of perspectives below from GIC voters illustrates some convergence in outlooks across investment teams over a potential decline in the dollar.

- One recent reference is the drop in the dollar index (DXY) in 2017 (when DXY dropped 10% over the year, during “Trump 1.0”), and there could be similar downside over 2025.

- The yen is surest to strengthen if the dollar does turn, due to the Japanese currency's significant under-valuation. The risks of sudden moves (amid an uncertain policy and market environment) persist and may be worth paying some premium to hedge against sudden dollar declines.

- Inflation is riding higher than expected, and the BOJ is expected to continue hiking; its tightening may include an intention to curb the yen's decline, which contributes to inflationary pressures.

- There are some significant risks of yen appreciation, particularly given the Trump administration's stance on trade. The yen remains under-valued/cheap, so there is potential for dollar/yen to adjust further.

- The long-standing US hegemony may be undermined by the current administration's policies, and the willingness of the rest of the world to export savings to the US may fall over time.

Currency outlook: The GIC foresees dollar/yen slowly falling toward 140 over the coming year, with an interquartile range of between 135 and 150 over the year to March 2026. We foresee narrower ranges but a gradual appreciation for euro/dollar , potentially breaking above the 1.1 level. We also expect a modest recovery by the pound , which is seen bouncing back above the 1.3 level versus the dollar. Additionally, we foresee the Australian dollar recovering above 0.65 versus the dollar over the next year.

Commodities: stronger gold, weaker oil

The current US administration made very clear that one of its main strategies to curb inflation is to rely on lower oil prices , upon which OPEC subsequently increased supply (in possible appeasement as to ward off potential tariff threats). The potential for weaker growth in the US may also weigh on oil prices. The GIC foresees the nearest Brent Crude future as slowly declining below USD 70 per barrel toward the USD 68 level over the next year; the projected range between the mid-62 to high 81 levels reflects uncertainty over the period. Meanwhile, as the magnitude of dollar predominance in global coffers comes increasingly into question, we expect continued support for gold , which is also recently proving to be a superior diversifier from US equity risk than Treasuries. The GIC expects the yellow metal to break above USD 3,000 per ounce, with an inter-quartile range of between 2,800 and 3,250 over the coming year.

Chart 8: Dollar dominance may be peaking

Demand for dollars by central banks

The US dollar's share in global foreign exchange reservers fell to its lowest level in 25 years in the fourth quarter of 2020, driven by exchange rates in the short term and central bank actions

in the long term.

(currency composition of global foreign exchange reserves, percent)

(US dollar share of foreign exchange reserves, percent)

(US dollar index, January 2006 = 100)

Sources: IMF Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER), US Federal Reserve Board, and IMF staff estimates.

Note: The "other" category contains the Australian dollar, the Candadian dollar, the Chinese renminbi and other currencies not listed in the chart. China became a COFER reporter between 2015 and

2018. See Arslanalp and Tsuda (2015) for an application of the methodology. Interest rate changes may also effect currency shares although these effects tend to be smaller. The US dollar index is

the Federal Reserve's Advanced Foreign Economy Dollar index. The bottom panel uses a different scale to focus on the US dollar share.

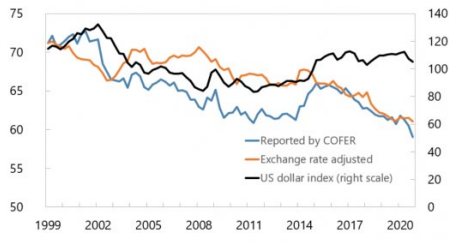

US valuation rebound likely capped; Japan, Europe, Asia-ex could rise further

Last quarter, despite our upbeat expectations for US earnings , we thought that valuations may have peaked, a trend which materialised in the first quarter of 2025. One voter remarked that “US exceptionalism” is already fully priced into the equity market and foresaw uncertainty over the US administration's policies as a factor that could impede valuation recoveries. Another voter pointed out that although the investment in AI fuelling much of the recent appetite for US stocks “is not by any means over”, there is a plateauing of the growth trajectory as new competitors enter the market. From a cyclical perspective, this could raise questions about the duration of the US expansion cycle, potentially causing some investors to hesitate before entering the US equity market at such a potential cyclical turning point.

While the GIC remains positive on US earnings growth over a one-year horizon, with the S&P still potentially achieving double-digit EPS growth, voters see recoveries in valuations in terms of price/earnings as limited. Voters see valuations staying on a downward trajectory even if there is a temporary recovery from current levels.

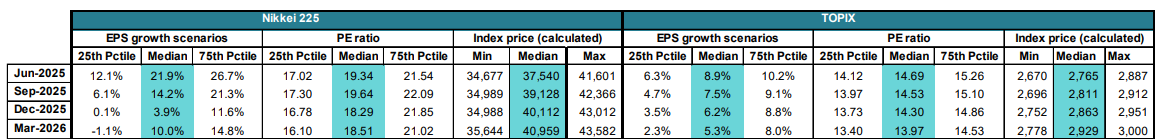

As we see in Chart 9, US stocks remain in the upper end of their most recent 20-year valuation ranges, even after the recent correction. Japanese stocks meanwhile remain firmly in the lower end of their valuation ranges, suggesting that markets have been slow to reward the improvement in firms' earnings growth. On a day-to-day basis, we note that foreign investors continue to dominate trading on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, and some of them are still betting on the relationship between dollar/yen and the Nikkei 225. But we have also seen dips amid recent volatility (when many of these foreign investors unwind their leveraged positions) where domestic investors have stepped in to buy and hold these securities. The domestic investors include Japanese corporates (buying back their own shares and thereby boosting ROE), households (turning their monumental cash savings into investment) and institutional investors (rebalancing portfolios).

Although the dollar/yen may drop to 140, we also note that as the composition of Japanese growth has turned more domestic, Japanese equities have recently become less sensitive to currency movements. Domestic consumption remains a buffer against external demand shocks and is also a beneficiary of a rebounding yen. All of this may point to the diversification value of Japanese equities within a global portfolio. The GIC foresees EPS growth staying positive among TOPIX constituents despite gradual BOJ rate hikes and pressures from external trade. The GIC also expects P/E ratios to experience dips over the next year. The result may be a gradual trend improvement in the price of the index and its constituents, punctuated by periodic two-way swings. Similarly, despite the potential for significant volatility in the Nikkei (in which foreign holdings typically concentrate), we expect earnings to stay positive and therefore help the index, thereby contributing to modest gains over the year.

Of course, such improvement is contingent upon the “virtuous circle” of wages and prices remaining intact and domestic growth continuing even amidst a high inflation rate of 3%. The latest Shunto negotiations suggest the possibility of near-record wage increases, which are crucial for to keep the economic cycle going. This could help cast rate hikes in a more positive light, given the BOJ needs to control inflation in 2025 to keep real wages in positive territory.

Chart 9: US valuation less exceptional but still relatively high

Source: Nikko AM Global Strategy, Macrobond

Regarding Europe , we expect a pivot toward low but solid positive earnings growth, which may help European stocks capitalise on some of the recent valuation re-ratings. We note that despite the rebound in valuations (see Chart 9), European and APAC ex-Japan stocks remain firmly in the middle of their most recent 20-year valuation range, which suggests that there remains room for positive earnings to be rewarded.

Risks to our outlook: US policy risks loom, possible upside risk in Europe

Although we have already touched upon some of the risks associated with a potential US recession, we highlight below some of the policy-related risks our voters highlighted. These risks have prompted many voters to elevate tail risks to a higher probability than the prior quarter.

- DOGE tactics of “shrinking” the US government: while the idea of making the government more efficient may be worthwhile, the current administration's tactics have proven chaotic. However, there are some early indications that the rule of law remains and that US pluralism is still likely to be able to provide checks and balances in the face of potential challenges. One critical factor is whether legal recourse is successful in limiting the power of unelected officials and the executive branch when their actions threaten to undermine the balance of power with the legislative and judicial branches. Our base case is that the US will be able to maintain the rule of law, even if there is uncertainty in the short term. However, failure to maintain the rule of law may cause significant damage to the US economy, potentially accelerating the possibility of a recession and negatively affecting global growth.

- Trade tensions: Our base case is that the ongoing trade tensions will not escalate into full-on trade war, and that the US is engaging in strategic behaviour and will back down once it achieve its desired payoffs. That said, these payoffs are not yet entirely clear. Furthermore, uncertain payoffs typically lead to less certainty of optimal outcomes from a game theoretical perspective. It is rational to assume that the desired payoffs are not the full sabotage and destruction of the US's trade partners and relationships. In scenarios where a high-stakes game allows for irrational outcomes, there is a risk of mutual escalation, which could have detrimental effects on global growth. Voters assigned subjective probabilities ranging between 20 and 25% to the possibility of trade tensions escalating into a trade war.

- Stagflation risk: the economy may start to weaken while tariffs contribute inflationary pressure, especially if trade tensions escalate into a full trade war. In such a situation the negative impact on real growth can be substantial. While this is not the central scenario, the probability of this outcome occurring has been rising in the tail. Some participants put the probability at 25%.

- NATO and the dissolution of the postwar order: Geopolitical uncertainty has been heightened by US threats to exit NATO. That said, these threats, much like trade negotiations, could be designed to extract concessions such as greater military spending from other NATO members. The possibility of the US looking to extract concessions carries lower risk than that of the US actually leaving NATO. Regional security agreements play a significant role in supporting the US's “exorbitant privilege” of seignorage and the dollar's reserve currency status. Any break in these agreements could undermine this privilege and erode trust in US assets. This, in turn, could drive foreign investors to demand higher premiums for financing the US current account deficit.

- Upside risk in Europe: Even as the US takes unconventional measures to cut government expenditure in attempt to increase efficiency, Europe is increasing stimulus and stepping up spending on defence. In the event of a Ukraine ceasefire, the decrease in political violence plus increase in domestic spending may be very supportive. There of course remains the countervailing risk that a ceasefire may not be achieved.

Long-term growth: What to make of US policy risk? Why uncertainty may persist

One question that voters asked at the GIC at the conclusion of the discussion of tail risks was how to assess the high-stakes game associated not only with US trade but also the controversial actions of the DOGE. On US Trade, the analysis, as noted in the “Risks” section, probably rests on (a) how speedily unknown payoffs associated with tariff measures (and retaliation) will become known in time and (b) whether “cheap talk” (communication with no payoff) will guide trade partners toward a more optimal equilibrium. As (a) becomes clearer, so may our ability to evaluate (b).

Assessing the risks of domestic policy, particularly given the ongoing rewriting of the rules of the US policy “game”, remains more complex. It may be said that the initial expectations formed by market participants over “government efficiency” appear to differ substantially from measures actually delivered to date. Judging by the initial out-performance among smaller-caps following the recent election victory by President Trump, markets appear to have anticipated an improvement in ease of doing business for smaller firms that lack scale but employ the majority of US workers but are most typically disadvantaged by regulations. In this respect, actual policy implemented to date appears to have been a significant shock.

That said, if targeted measures are actually implemented to reduce barriers to entry in highly regulated industries, such a policy move could deliver a productivity boost. An analysis of deregulation in Japan, where regulations tend to be more stringent across many industries compared to the US, shows that reducing the number of industry regulations may have positive impact, particularly where regulation is high and productivity is low. However, the benefits of deregulation may be less pronounced in industries that are already deregulated or demonstrate higher productivity growth. Unlike monetary policy, deregulation is a more precise tool.

In the US, where total factor productivity growth has been relatively low, measures designed to lower barriers to entry among small and midsize businesses in sectors where entry is difficult could help stimulate productivity growth. Simplifying paperwork for such businesses, and lowering operational risks associated with market entry may make it easier for smaller firms to compete. We are still in the early days of the new US administration and therefore cannot completely rule out the potential shift toward such strategic deregulation.

Separately, regarding structural risks surrounding US institutions, it is helpful to refer to the work of 2024 Nobel Prize winner, economist Daron Acemoglu. In “Why Nations Fail” (2012), Acemoglu identified specific characteristics that distinguish successful national institutions from less successful ones across centuries and geographies. The successful institutions gave rise to sustainable growth and capitalised on critical junctures of historical change and innovation. Their common characteristics included a centralised government (standardising laws and infrastructure), pluralistic institutions with checks and balances, and rule of law which gave rise to inclusive rather than extractive economic growth. Therefore, in order make deregulation meaningful, we must assess whether national institutions are incentivizing (inhibiting) widespread economic participation by decreasing (increasing) barriers to entry and competition. Decreasing barriers to participation is what is meant by inclusive growth. One historical example of this was the ability for individuals to apply for patents and loans to commercialise their innovations during Britain's Industrial Revolution. This allowed British growth to outpace that of many of its neighbours with less inclusive national institutions, at a critical juncture in history, characterised by rapid technological innovation.

Once again, we are still in the early days of the current administration and challenges to centralisation, pluralism and inclusive growth may ensue before we can conclude whether policy risks to growth are likely to subside. It is possible that only with time, as precedents are established, we can gain a better understanding of the sustainability of longer-term US growth.

Investment strategy conclusion: cycle extension but with downside protection

While our central scenario is for US growth to remain positive over the coming year, we have downgraded our GDP growth outlook for the US. Meanwhile, with the US “exceptionalism” narrative fading, we see value in global diversification, even while maintaining US assets within a global portfolio. We expect Japan's “virtuous circle” to remain intact and improving wages to support domestic consumption and provide a buffer against swings in external demand. Even though our central scenario is for slower but continuing US growth, the risk of recession has risen substantially alongside the uncertainty surrounding the risks associated with policy disappointments. Risks appear to be biased towards inflation, and we continue to foresee attempts at expansionary US fiscal policy provoking inflationary concerns and potentially leading to a rise in long-term yields.

We still favour holding stocks to protect the future purchasing power of investors. But we see a case for diversifying risks across geographies and asset classes to mitigate the cyclical risks that stocks are sensitive to. In this context, shifts in respective fiscal policies in Europe and China may provide opportunities for earnings growth and therefore supporting future valuations. We continue to favour rotating exposure towards Japanese domestic demand-related stocks. Signs of a sustainable structural recovery and reduced correlation with the US may enhance the diversification value of Japanese stocks.

At the same time, the re-rating of bond markets may create new opportunities to diversify into global bond markets and reduce the allocation to US Treasuries. This shift is supported by the stabilising of electoral uncertainties in economies such as France and Germany, as well as the settling of the leadership crisis in South Korea. Despite its low yield, we continue to see the yen as a risk haven that offers downside protection in the event of an equity market correction. We continue to favour gold, although its valuation has risen significantly in large part because of its diversification value.

The GIC's guidance ranges may be found in Appendix 1 of this document.

A note on changes to the Global Investment Committee Process: In June 2024, we made changes to the Global Investment Committee, as to align our quarterly Outlook more closely with the views underlying our portfolio investments. In lieu of forecasts, we have chosen to provide guidance ranges for indicators and indices that we feel most closely relate to the asset classes we manage. In place of forecasts the Global Investment Committee now provide aggregate guidance at the median for our central outlook, and at the 25th and 75th percentiles.

The asset classes represented in our Outlook can change over time, depending on what is most representative of our active investment views.

In the event full ranges are not available, this may be interpreted as to mean that the asset class is not a central focal point for our highest conviction investment views.

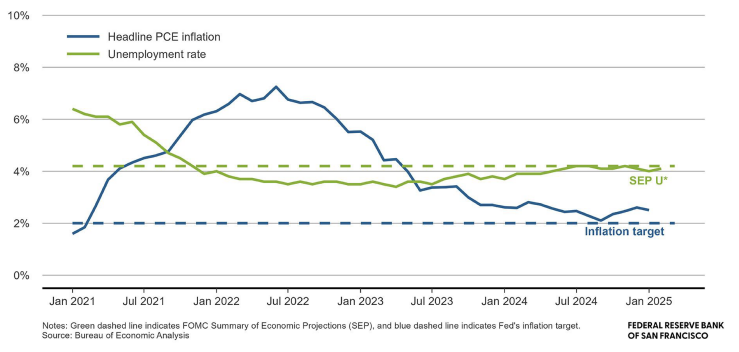

Appendix 1: GIC Outlook guidance

Global macro indicators

Central bank rates, forex, fixed income and commodities

Equities