Asia’s healthcare story

The demand for healthcare services and products shows no signs of abating. The global population is ageing, while more people are at risk of developing chronic diseases such as diabetes and cancer. The need for medical treatments and preventive health services has also increased, as people live longer and lead more active lives. Nowhere is this need more apparent than in Asia. The region is home to more than 4.5 billion people, and its growing and ageing population demands access to better healthcare services and innovative, affordable and accessible medicines.

The imperative for healthcare investment in Asia has only accelerated following the COVID-19 pandemic. While governments across Asia have each responded differently to the immediate threat and longer-term implications of COVID-19, throughout the region there has been similar recognition that investment cannot be delayed. As China has discovered since emerging from its “zero- COVID” lockdown regime, the socio-economic costs of being slow to develop medicines and vaccines—and to distribute those medicines across an entire population effectively—are simply too high to bear.

A decade-plus of healthcare investment is bearing fruit

The good news is that as a collective bloc, Asia’s response to the healthcare challenge bears strong similarities with its investment into technology dominance some 30 years ago. In the 1990s, the manufacture of integrated circuits, microprocessors and other semiconductor components was dominated by foundries in the US and Europe. But as new technologies increased the demand for semiconductors, investment and innovation within China, Taiwan, and South Korea shifted the dynamic greatly. Over a span of 30 years, Asia has become the global foundry powerhouse, dominating the semiconductor industry with its market share exceeding 85%1.

1TrendForce as cited in press release, April 25,2022

Figure 1: Total integrated circuit ex memory revenue (US dollar [USD] million)

![Total integrated circuit ex memory revenue (US dollar [USD] million)](/files/images/articles/2023/2304_asias_healthcare_opportunities_01.png)

Source: Gartner, Credit Suisse Securities

The healthcare sector in Asia has undergone a similarly dramatic transformation over the last decade, and much of that began with government investment borne from a desire to make healthcare in Asia a true global leader. Government policies, incentives, and strategic prioritisation has resulted in a thriving healthcare industry in Asia. Across the region, governments have encouraged private sector investment and public-private partnerships. They introduced new regulations and standards to encourage innovation in biomedical sciences and ensure a high standard of care; furthermore, they promoted digital health technologies to serve rural and previously underserved areas. However, while government investment and policy have played a decisive role in jumpstarting Asia’s healthcare advances, it is Asia’s private companies that are seen to be dominating the healthcare landscape and taking innovation to the next level.

Extensive and relentless research and development (R&D) efforts coupled with major advances in medical technology have enabled the development of new treatment modalities, greatly improving clinical outcomes. In addition, Asia’s key role in the global manufacturing supply chain of medicines as well as the rise in demand for outsourced research, development and manufacturing services uniquely positions the region to capitalise on the growth opportunities in healthcare.

Drug manufacturing and ingredients

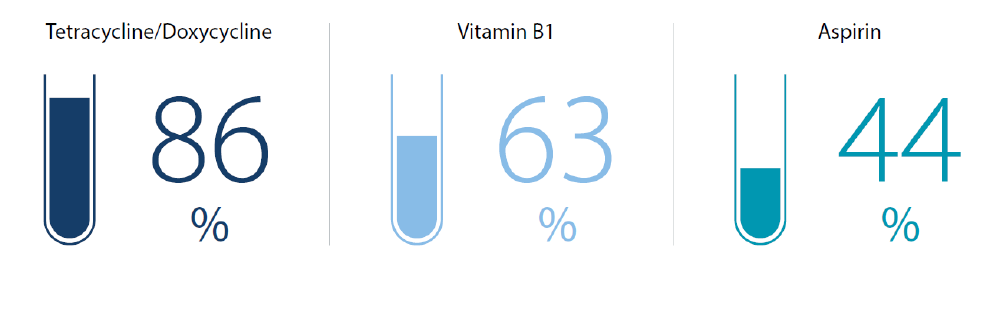

Until the 1990s, the west and Japan produced 90% of the active chemicals used in drug manufacturing, also known as “active pharmaceutical ingredients” (APIs). Such ingredients are sourced from chemical suppliers and formulated into a final dosage form such as a tablet, capsule and injection. However, Asia’s decade-long investment in the pharmaceutical industry, and its increasing ability to manufacture consistent, high-quality APIs meant that by 2020, the region was producing more than 60% of the world’s APIs. China alone accounted for the bulk of exports of several key pharmaceutical raw materials, and—according to Nikkei Asia—was by then already playing “an indispensable role in the supply chain for antibiotics and vitamins”.2

Figure 2: China’s share of global exports of key pharmaceutical ingredients in 2020, by volume

Source: Nikkei Asia, Trade Map (data may contain chemical compounds for other uses)

2https://asia.nikkei.com/static/vdata/infographics/chinavaccine-3/

Global demand for generic medicines

Generic medicines contribute significantly to expanding access in healthcare and have a critical role to play in lowering healthcare costs in both developed and developing countries. Generic drugs are made with the same APIs as brand-name drugs, but they can be distributed to consumers at a significantly lower cost after the patent or exclusivity period for a brand-name drug expires. The US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) estimates that 90% of prescriptions filled are for generic drugs.3

The key factor that is seen making a generic drug competitive is its affordability. Although generics make up 90% of prescription volumes, generic drugs, by value, are estimated to comprise just 23% of global pharmaceutical spending. Increasing the availability of generic drugs helps create competition, which improves the affordability of treatments and expands access to healthcare for more patients. Generic drugs also help make the pharmaceutical industry more competitive, ultimately leading to more innovative medications and better patient outcomes.

India is the world’s largest exporter of generic medicines and has one of the lowest manufacturing costs globally. It is cheaper to manufacture generic prescription drugs in India due to the availability of low-cost labour, lower regulatory costs and the presence of large, well-established pharmaceutical companies. Over time, the Indian pharmaceutical industry has built scale and then further lowered costs through economies of scale. As a result, about one in three pills consumed in the US (and one in four in the UK) are made by Indian manufacturers. 4In 2021, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared the country’s healthcare sector had earned India the title of being the “pharmacy of the world”.5

Biologic medicine and biosimilars

The bulk of global pharmaceutical spending is on biologic drugs, which are made from proteins, nucleic acids and living entities such as cells and tissues. As opposed to chemically synthesised drugs whose structure is distinct and known, biologic drugs are often of a complex nature; for example, cell and gene therapies can treat genetic diseases, cancer and autoimmune diseases.

Understandably, biologic drugs require specialised production processes, making them more expensive to manufacture than standard chemical drugs. Because of the usually life-threatening nature of the medical conditions they are designed to treat, biologic drugs are also usually subject to extensive testing and screening procedures to ensure their safety and efficacy. As a result, biologic drugs require much more extensive testing and screening procedures than generic drugs. In addition, companies that produce biologic drugs have fewer competitors, enabling them to charge higher prices.

Similar in concept to generic drugs, biosimilars are versions of biologic drugs that have successfully demonstrated similar efficacy to the original biologic drug. The emergence of biosimilars is a result of the expiration of patent protection for some biologic drugs, which since 2015 has allowed several biosimilar companies in Asia to produce and compete with the original biologic drugs. Biosimilars have the potential to become an equally effective alternative to biologic drugs, and provide more treatment options at a more affordable price for patients worldwide.

HUMIRA is an injectable biologic drug manufactured by AbbVie, and it is used to treat autoimmune diseases such as Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. HUMIRA was granted FDA approval in 2002, and hence it is coming off-patent in 2023. It has since become the highest grossing drug in the world (excluding COVID vaccines) with global sales of almost USD 20 billion in 2021, according to Rx Savings Solutions. Patents for 17 other major brand biologics are set to expire over the next decade. With the number of pharmaceutical companies and research institutions in Asia increasing, there is the potential for a new generation of biosimilar drugs that can be distributed globally at a fraction of the cost of their original branded versions. South Korea’s “first wave” of biosimilars was approved in January 2018. We appear to be entering a “second wave”, where the same scenario plays out for biosimilars in the small-molecule generic drug space.

3https://www.fda.gov/drugs/generic-drugs/office-generic-drugs-2021-annual-report

Beyond generics and biosimilars: the market for innovation

Looking beyond generics and biosimilars, even more significant developments are taking place in Asia, driven by the universal need for better medicines. A big turning point for the healthcare industry as a whole—providing confirmation that healthcare in Asia is an investment megatrend—is that Asian companies are now developing potentially first-to-market, globally competitive and innovative drugs.

There are two major drivers behind the rise in Asian biopharma investment. The first is that the most prevalent diseases in Asia are associated with poor prognosis and higher mortality. One example is in cancer. Asia accounts for 60% of the world’s population and half the global burden of cancer.6 But among the top five most prevalent cancers in Asia, three are considered orphan diseases in the west. As a result, very few “Big Pharma” companies are willing to make the R&D investments to develop innovative drugs for these cancers, given the small size of the patient pool in the US and Europe, not only because of the small market potential but also the difficulty in recruiting patients to run clinical trials. The second, and equally important, driver is that universal healthcare programmes have been rolled-out in key emerging countries in Asia, including China, Indonesia and Thailand. Additionally, commercial health insurance is starting to see rising penetration. Previously, many patients in developing Asian countries could not afford the latest innovative medicines due to the high cost of treatment relative to their income levels. The shift away from out-of-pocket payment is expected to solve the problem of affordability, creating a new pathway for Asian patients to gain access to better medicines with improved medical outcomes as well as a new market for innovation in Asia.

The rise of Asian CXOs

In the developed world, pharmaceutical companies have sought to reduce their investments in large biologic processing plants due to the heavy capital expenditure (capex) involved. Instead, they have relied heavily on biologic contract manufacturing companies such as Swiss multinational Lonza and Germany’s Boehringer Ingelheim. This outsourcing trend has expanded from primarily manufacturing medicines to R&D.

Regarding outsourcing, the term “CXO” (“contract X organisation”) has recently come to describe a company that provides medical contract services. The X in CXO can be replaced by R (research), D (development) or M (manufacturing). CXOs can be called upon by pharmaceutical companies to provide contract services for R&D, to manage and run clinical trials and to manufacture and commercialise medical products.

South Korea’s Samsung Biologics and China’s WuXi Biologics both emerged as biologic CXOs at about the same time roughly ten years ago. Both have built massive R&D capabilities in areas such as monoclonal antibodies used in the treatment of cancer, autoimmune diseases and inflammatory diseases. These CXOs have gained market share by building unrivalled expertise in process technology, process patents and deliverance of faster time-to-filing of investigational new drug application approval to the submission of final biologic license application for regulatory approval. Samsung Biologics’ clients include GSK, Janssen (of J&J), Merck, Eli Lilly and AstraZeneca. More recently, GSK entered into an agreement with WuXi Biologics where GSK will acquire licenses for up to four bi- and multi-specific T cell7-engaging antibodies developed using WuXi Biologics’ technology platforms. The aim is to provide GSK with access to potential best-in-class antibodies that are effective in killing tumours.8

Back to our semiconductor parallel, we may think of CXOs such as Samsung Biologics seizing market share in biologics manufacturing in the same way as TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) becoming the world’s largest dedicated independent foundry. But it is important to recognise that Samsung Biologics is not just competing on cost, as with TSMC.

Of course, some challenges to this new operational dynamic persist. The pandemic brought to the surface the risks of over-dependence on a single source for critical parts of the global supply chain. This applies within technology as well as in medicine. In addition, geopolitical risks have increased over the past few years, especially the rivalry between the US and China. The CHIPS and Science Act passed by the US in 2022 has changed the playing field by using legislation to bring semiconductor manufacturing back to the US, and it would be naive to think that the healthcare industry would not be subject to such regulatory changes. Even so, when it comes to healthcare, strengthening international cooperation and collaboration to promote global health would benefit all. If there is one thing the world has learnt from the pandemic, it must be the importance of trust and global cooperation.

Any reference to a particular security is purely for illustrative purpose only and does not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security. Nor should it be relied upon as financial advice in any way.

6https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4029284/

7A type of white blood cell that recognises and attacks harmful invaders.

Summary

Asia still faces many challenges in improving its existing healthcare infrastructure. But the investment made by governments in Asia over the past decade is beginning to bear fruit. The number of healthcare-related companies in Asia’s investible universe is expanding every year. Even so, healthcare still represents a very small percentage of Asia ex-Japan equity markets, suggesting this is an opportunity the rest of the world has yet to recognise or put a fair value on. Asia managed to dominate the semiconductor industry in one of the biggest success stories of the last 20 years. Investors can perhaps ask themselves whether Asia can also dominate healthcare over the next two decades with its blend of innovation, scale and high sustainable returns.